STUDENT-CENTRED TEACHING

… a pedagogical approach which gives learners, and demands from them, a relatively high level of active control over the content and process of learning. What is learnt, and how, are therefore shaped by learners’ needs, capacities and interests. (Schweisfurth 2013: 20)

Orientation

Much educational discourse (the frameworks, values, ideals and aspirations) in higher education is dominated by the idea of student-centred teaching 1 . Tagney (2014:267) suggests correctly that the term ‘student-centred learning’ is ‘ubiquitous throughout the pedagogic literature’ and that it ‘appears in many university strategic documents.’ In discussing the origins of the term, Tagney notes that many identify Rogers as the origin of student-centred learning. Rogers and colleagues, Tagney explains, talk about ‘learning which is meaningful, experiential and focused on the process rather than the product,’ or whole-person learning. (Tagney 2014:

266) Certainly, Biggs and Tang (2011) assume the value of student-centred teaching and, indeed, position the need for student-centred teaching as the driver for outcomes focused teaching and criteria referenced assessment in their modelling of constructive alignment.

This paper is designed to:

Provide a brief critical overview of student-centred Teaching. (This overview is critical in the sense that it takes a questioning stance in relation to the principles and practices of SCT. This is not done to dismiss or diminish the approach but, rather, to provide a practice-focussed, critical realist perspective that will make learning experiences at CIHE more salient to students and therefore more facilitative of their success.)

Outline the way in which student-centred teaching informs pedagogical design and delivery at CIHE, and

Address some key issues for CIHE in our use of a student-centred approach to teaching and learning.

Some theoretical background

In discussing the theoretical origins of student-centred teaching, Tagney identifies ‘some similarity between the language associated with constructivism and that associated with writings on student-centred learning,’ and specifically notes ideas such as ‘purposeful active engagement,’ ‘discovery learning,’ ‘creating one’s own understanding,’ ‘building on prior knowledge,’ and ‘reflection and creating dissonance.’ She also notes, by contrast, that ‘ideas such as empowerment and emancipation that also feature in writing about student-centred learning are not generally discussed by constructivists; these are more aligned with humanist conceptions of learning.” (Tagney 2014: 267, emphasis added)

Constructivism

Hussain 2012 describes constructivism as the ‘theory which emphasizes on (sic) providing opportunities to students for making their own judgments and interpretations of the situations (they come across) based on their prior knowledge and experience’ and goes on to explain that the theory ‘is based on active involvement or participation of students in teaching learning process (sic). It aims at developing skills among students by offering to them activities and projects in their relevant disciplines and contexts.’ (179)

Gilis and her colleagues (2008) suggest that the change of focus from the teacher to the student ‘has followed the increasing importance of constructivism in higher education. (532) Constructivism, they explain, ‘explicitly states that learning only takes place when it is meaningful for the learner. The different streams [of constructivism] have in common the centrality of the learners’ activities in creating meaning, as they actively select, and cumulatively construct, their own knowledge, through both individual and social activity.’ (Gilis et al 2008: 532) They explain further that, this view on learning ‘results in a pedagogy focusing on an approach to teaching that effectively supports students in the process of meaning construction.’ (Gilis et al 2008: 532, emphasis added) All pedagogical discourses that position themselves as constructivist ‘argue for a learning paradigm ending the teacher’s privileged position’ and claim that a ‘student-centred approach to teaching proves to be more efficient in order to support students in this process of meaning construction’. (Gilis et al 2008: 532, emphasis added) Biggs and Tang offer a historical perspective in their description of student-centred learning that elucidates the idea of meaning construction:

Constructivism has a long history in cognitive psychology, going back at least to Piaget (1950). Today, it takes on several forms: individual, social, cognitive, postmodern (Steffe and Gale 1995). All forms emphasize that the learners construct knowledge with their own activities, and that they interpret concepts and principles in terms of the ‘schemata’ that they have already developed. Teaching is not a matter of transmitting but of engaging students in active learning, building their knowledge in terms of what they already understand. (Biggs and Tang 2011: 22)

Meaning construction on the part of students is central to constructivist pedagogy as is the idea, informed by the work of Vygotsky (see Harland 2003), that learning is staged and is best developed from existing schemes or known systems of meaning. This idea has translated into the contemporary focus on learning outcomes and other components of constructively aligned teaching and student-centred teaching. Deploying one of the key binaries that structure the ideas of student-centred learning, Gilis et al. conclude their discussion suggesting that ‘such an approach puts emphasis on helping students to learn and on students’ learning outcomes, whereas a teacher-centred orientation focuses on the transmission of defined bodies of content and knowledge.’ (Gilis et al. 2008: 532)

Humanism

Humanist ideas of empowerment and emancipation are explored a critical discussion of humanist education by Bingham (2016). Below, Bingham is giving an account of the way in which humanist educational theorists – Dewey and Freire – position their calls for emancipatory pedagogy against humanist-led interpretations of ‘traditional’ pedagogies and/or their modes.

In schools, those under instruction are too customarily looked upon as acquiring knowledge as theoretical spectators, minds which appropriate knowledge by direct energy of intellect. The very word pupil has almost come to mean one who is engaged not in having fruitful experiences but in absorbing knowledge directly. Something which is called mind or consciousness is severed from the physical organs of activity (Dewey 2008, Chpt 11). (From Bingham 2016: 183 citing Dewey)

In this account, the ‘whole of person’ approach discussed by Tagney is clearly a humanist ideal and drives the requirement for experiential learning. Below, Bingham provides a brief account of Freire’s critique of modes of instruction as captured by the pejorative ‘banking metaphor.’ The idea that this interpretation of students being compelled to memorise content in instructional content-delivery modes is the negative term in the much-used binary that positions student-centred teaching against teacher-centred teaching.

Like Dewey, Freire bemoans the predominant modes of teaching and learning in which the student is generally treated as a spectator. For Freire, a critique of spectatorship is not a comment on traditional education, but rather a way to expose the ‘‘banking system’’: “The banking concept (with its tendency to dichotomize everything) distinguishes two stages in the action of the educator. During the first, he cognizes a cognizable object while he prepares his lessons in his study or his laboratory; during the second, he expounds to his students about that object. The students are not called upon to know, but to memorize the contents narrated by the teacher” (Freire 2005, 80) (Bingham 2016: 184)

One of the key limitations of the rise and dominance of the discourse of student-centred teaching is the under- critiqued mobilisation of binaries that pit the student-centred teaching ideal against the negatively constructed and viewed forms of teacher-centred pedagogy. Interested staff are encouraged to read the critical literature which addresses these questions. For now, it is perhaps useful to provide an account of the binaries typically used to value student-centred teaching.

Definitions and a CIHE refinement

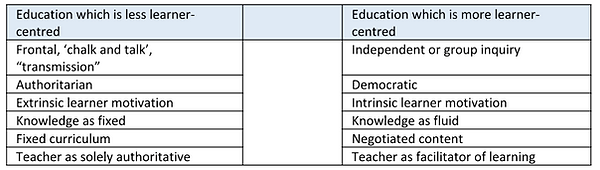

Here at CIHE, we see the binaries typically used to distinguish student-centred from teacher-centred teaching more as continua. Using the work of Schweisfurth, we work with a dynamic model that allows staff to articulate the choices of pedagogical modes they make in practice as part of our more elaborated approach to constructive alignment.

Michele Schweisfurth (who refers to student-centred teaching as learner-centred education) lays out the stark definitional contrasts:

TCE refers to the practice of teachers in transmission-focused classrooms. The teacher controls the content, level, pace and action. They are also the centre of attention in the class, for the majority of the time. ‘Chalk and talk’ is the colloquial phrase often used to describe this pedagogical mode, and lecturing and whole-class drilling are its typical practices. It is generally based on a fixed curriculum and the transmission mode described above, but the point is not what is taught, but how. In its extreme, learners are rarely free from the control of the teacher, and the learning is usually either whole-class or silent. By contrast, LCE gives more control to learners, not just over content, but over how they learn. In the learner-centred classroom, study involves collaborative interactions with other students, as well as the teacher. Individual interests, learning preferences and styles, and personal needs help to guide the process. Fixed curriculum, plus TCE, equals rote learning: anathema to purist advocates of LCE.

As we can see from these definitions and distinctions, the discussion on LCE is full of dualisms. (2013: 10-11)

In a very practical and realist way, Schweisfurth cuts across the binaries/dualisms that are used to demarcate approaches to teaching and to value one implicitly more highly than the other. Much more usefully, she considers the terrain of pedagogical method and mode a complex one that involves a mix of techniques, relationships and knowledge (more on these below). Before we consider the enactment of the pedagogical mix of techniques, relationships and knowledge in any real classroom, the table captures the ‘ends’ of the continua that Schweisfurth introduces in conceptualising a ‘more-or- less’ dynamic model of pedagogy:

Table 1: Schweisfurth’s continua

Developing a student-centred approach

In thinking about how to apply and work with Schweisfurth’s continua, McCabe and O’Connor (2014) provide a more focused and directive account of SCL:

A student-centred approach encompasses four fundamental features: active responsibility for learning, proactive management of learning experience, independent knowledge construction and teachers as facilitators.

(McCabe and O’Connor (2014: 351)

This orientation leads to an ‘… alteration to the respective authoritative-passive roles of teacher and student’ and this ‘represents a new cooperative relationship,’ providing for learning that takes place ‘in a constructive interaction between the two groups (Attard et al. 2010, 4)’ (McCabe and O’Connor (2014: 351) Quoting research that suggests a student-centred approach leads to deep learning, they argue that the teacher student interface should be ‘characterised by a range of variables,’ including: teacher orientation; teaching behaviours; assessment; and feedback ( McCabe and O’Connor 2014: 351 ). It is useful to consider each of these aspects to one’s teaching practice in the planning, delivery and reflective stages of your teaching work.

McCabe and O’Connor further suggest that a ‘successful student-centred approach requires a collective organisational, philosophical and pedagogical shift,’ and that the ‘readiness of teachers is pivotal and research has identified common difficulties, including limited preparation, competing timetables, resistance from other staff, student reluctance and lack of confidence.’ They conclude that ‘any re-alignment of curriculum should identify those variables that nurture the teacher–student dynamic.’ (McCabe and O’Connor 2014: 351 )

In applying a more dynamic approach to student-centred teaching at CIHE, the remainder of the paper offers some practical thinking and planning first by considering how it is that ULOs help use adopt a student-centred approach to our teaching and then by thinking about how we might design teaching learning activities in line with the principles of student-centred learning. The design and delivery of assessment within our overall framework and in line with the principles of student-centred teaching is addressed in the series of assessment papers.

Learning outcomes

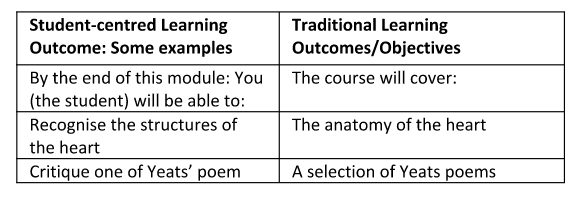

The table below is presented by O’Neill et al. (2005) What it captures is the key distinction between 1. (on the right) content as ‘knowledge’ – what students can recall or what they are considered to know coded into nominal structures that describe abstract things (areas of knowledge) and 2. (on the left) a sense of action, activity or doing coded into the use of a verb phase ‘will be able to recognise…’ etc. This language shift signals a shift of focus to student capacity or capability, rather than thinking about knowledge as object or possession. This perspective is a good one to adopt right from the moment we begin to consider what we teach because it makes what we teach as question of what we want students to be able to do.

Table 2: ULOs and student-centred learning from O’Neill et al 2005: 30

Teaching Learning Activities

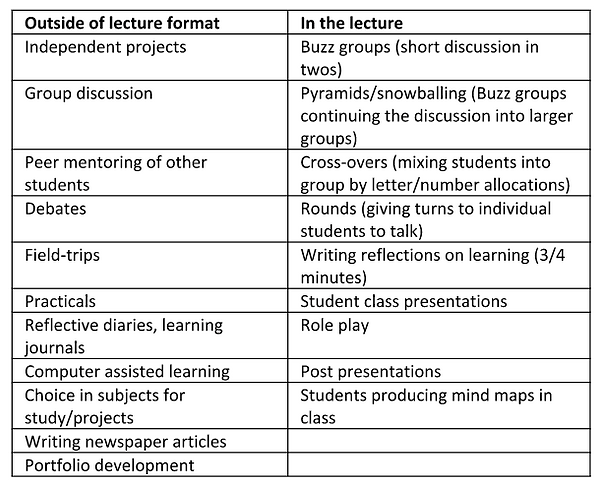

The shift from the question of what we teach to question of what we want students to be able to do instigates another shift to the crucial pedagogical question: ‘How can we help students learn how to do what we want them to do?’ Most of us rarely teach by simply telling students what they need to know and expecting them to learn this ‘content.’ The question ‘How can we help students learn how to do what we want them to do?’ asks us to think critically about our pedagogy. We can do this using Schweisfurth’s categories: techniques, relationships, motivation and epistemology (knowledge):

Epistemology, of course, has to do with ‘the nature of knowledge – whether it is a fixed body of information that can be bounded, described and taught, or whether it is fluid, changing over time and subject to interpretation.’ (Schweisfurth 2013: 12)

With respect to her dimension of technique, Schweisfurth suggests that student centred teaching ‘is about what teachers do with learners in classrooms’. She gives examples of group work, independent inquiry, project- or problem-based learning and ‘scaffolding’ based on the needs of individual learners. (Schweisfurth 2013: 12)

With respect to relationships, Schweisfurth suggests that there is a range of possible relationships between teachers and learners along the continua ‘authoritarian to more democratic.’ (Schweisfurth 2013: 13).

About motivation, Schweisfurth suggests that ‘[i]n order for learners to work independently or in groups without constant intervention or leadership from the teacher, and in order for them to abide by democratic principles rather than relying on the rewards and punishments of the authoritarian motivational repertoire, they need to be intrinsically motivated, and believed to be so by their teachers. (Schweisfurth 2013: 13) The continua above articulate these dimensions and are interdependent.

Table 3: Examples of student-centred methods from O’Neill et al, 2005: 31

In thinking about their pedagogy, especially their classroom practice, staff are encouraged to consider a rudimentary analysis of their teaching and learning activities using the continua and the dimensions these articulate. It should be noted that the column headings ‘in and outside of the lecture format’ are less useful as starting points; methods can and do cross these physical contexts. Staff should consider their pedagogical methods or modes at a more micro level. For example, group discussion can be seen as involving flexible constructions of knowledge (knowledge being negotiated), as a technique for student-student oriented learning in which students work with high levels of independence. This method is assumed to be more intrinsically motivating but most certainly this technique would rely on intrinsic motivation for its success. Role plays would perhaps be interpreted as even more intrinsically motivating (reling on intrinsic motivation), involving more flexible, dynamic and negotiated knowledge constructions and as an opportunity for high levels of student independence and autonomy.

This brief discussion is designed to stimulate thinking and discussion.

Key Issues for student-centred teaching at CIHE

In looking more closely at the critical scholarly literature that considers SCL, four issues are worthy of note and attention for us at CIHE:

Flexibility and mobility for staff: Student-centred teaching is an overarching orientation here at CIHE rather than a mandated set of limited practices. This paper and the approach here at CIHE is designed to support staff in making professionally informed decisions about their teaching. Schweisfurth’s continua are provided as a way to consider and discuss the approach and methods that staff use – a device for articulating their informed decisions about how to support student learning at different times and at different stages of their development. Sometimes teacher-centred teaching is necessary to achieve required learning outcomes. Clear, reasoned judgements should be made and documented through the constructive alignment tools.

Cultural specificity: There is much literature now that identifies the Western-centric nature of student-centred teaching, that is, that student-centred teaching is built on a set of assumptions about the culturally aquired predispositions of students. It may well be the case that some cohorts of students at CIHE are not ‘at home’ in certain educational modes. This requires a watching brief. We have a Diversity and Equity Policy and a Teaching and Learning Plan that require that we work in a way that supports the learning of diverse student groups. Some students will take time to adapt to student-centred teaching. Staff are encouraged to use the discussion in this paper to consider how they work with specific student groups and how they might support students in being more at home in student-centred teaching environments.

Monitoring and evaluating: This paper and our approach to student-centred teaching at CIHE are intended to be working frameworks, used, adapted and developed through the monitoring and evaluation. Staff are asked to keep records and to discuss openly and collaboratively the decision making and their reasoning, especially in terms of 1. and 2. above so that we can work collectively through reflexive practice.

Reflexive practice: It is hoped that here at CIHE we will develop a community of practice in which our teaching and learning work and our critical reflections on and developments of our pedagogy is shared, evaluated and developed in collaborative and mutually supportive ways.

David McInnes

August 2017

1 Also described as learner-centred teaching or student-centred learning. The term used at CIHE is student-centred teaching to imply student-centred teaching and learning. As will become clear as this paper progresses, the learning experience provided to students and our approach to teaching (design and delivery) are inter-dependent in the production of a student-centred experience mobilised within a framework of constructive alignment.

REFERENCES

Bingham, C. (2016). Against educational humanism: Rethinking spectatorship in Dewey and Freire. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 35(2), 181-193.)

Dewey, J. 2008. Democracy and education. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/852/852-h/852- h.htm.Ch. 11).

Freire, P. 2005. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Gilis, A., Clement, M., Laga, L., & Pauwels, P. (2008). Establishing a competence profile for the role of student-centred teachers in higher education in Belgium. Research in Higher Education, 49(6), 531-554.

Harland, T. (2003). Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development and problem-based learning: Linking a theoretical concept with practice through action research. Teaching in higher education, 8(2), 263-272.

Hussain, I. (2012). Use of constructivist approach in higher education: An instructors’ observation. Creative Education, 3(2), 179.

Lea, S. J., Stephenson, D., & Troy, J. (2003). Higher education students’ attitudes to student-centred learning: beyond educational bulimia?. Studies in higher education, 28(3), 321-334

McCabe, A., & Connor, U. (2014). Student-centred learning: the role and responsibility of the lecturer. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(4), 350-359.

O’Neill, G., Moore, S., McMullin, B. (2005). Emerging Issues in the Practice of University Learning and Teaching. (Eds). Dublin:AISHE, 2005.

Schweisfurth, M. (2013). Learner-centred education in international perspective: Whose pedagogy for whose development?. Routledge.

Schweisfurth, M. (2017). Learner-centred education in international perspective. Journal of International and Comparative Education (JICE), 1-8.

Tangney, S. (2014). Student-centred learning: a humanist perspective. Teaching in higher Education, 19(3), 266-275.