CONSTRUCTIVE ALIGNMENT AT CIHE

Evaluating Constructive Alignment in Units at CIHE A toolkit for staff

Overview

Constructive Alignment (CA) describes the process of pedagogical design in which the intended learning outcomes of a unit are mirrored both in teaching and learning activities and the assessment.

The constructive alignment of units at CIHE is a requirement of their design, delivery, monitoring and continued improvement. This toolkit provides an explanation of the principles of CA, its application to unit development and delivery at CIHE and the monitoring and continual improvement of CA as a quality assurance process. At CIHE we are compelled by the TEQSA accreditation process to use a model of constructive alignment. However, it is by far and away the best way to assure quality in the delivery of explicit, student oriented and outcomes-based undergraduate education.

According to Biggs and Tang, the term constructive alignment arose from the pedagogical reflections and experiments of Biggs in the early 1990s. Two principles were involved, each captured by the two terms used:

Constructive: Is drawn from the constructivist theory of learning. In this approach, leaners ‘use their own activity to construct their knowledge as interpreted through their own existing schemata’ (Biggs and Tang 2011: 97) Aligned: To signal the alignment of learning outcomes with assessment and teaching learning activities.

Constructively aligned teaching systematizes what good teachers have always done: they state upfront what they intend those outcomes to be in the course they teach. (Biggs and Tang 2011:99)

The alignment is achieved by ensuring that the intended verb in the outcome statement is present in the teaching/learning activity and in the assessment task. (Biggs and Tang 2011: 98)

This toolkit is organized into 3 parts. Part 1 addresses the writing of unit learning outcomes (ULOs). Though this is typically done at CIHE by the Course Advisory Committee and the Academic Board, staff may be involved in the development of ULOs and most certainly will be involved in unit review and improvement. It is vital staff understand and are able to engage in the first step of the process of developing constructively aligned units. Part 2 addresses the alignment of teaching learning activities (TLAs) with ULOs as one of the 3 vital aspects to CA. It provides a developing and monitoring tool that staff are to use in the units they teach each semester. Part 3 addresses assessment – its design and delivery as constructively aligned. Part 3 also contains an assessment development and monitoring tool.

Part 1: Learning Outcomes and Constructive Alignment at CIHE

This short guide provides an explanation of how Unit Learning Outcomes (ULOs) operate as part of unit design, delivery and our ongoing academic and educational quality assurance at CIHE. It is to be used in tandem with other material in this kit and in the Assessment at CIHE papers.

Following the definitions below, this guide initially explains the process of unit and course development and where, when and by whom ULOs are developed, refined and approved. The guide then outlines the conceptual and pedagogical framework for ULOs used at CIHE and then describes how staff might go about writing learning outcomes for a specific unit

Definitions

Unit Learning Outcomes

A statement or statements of what students should be able to do at the end of a unit of study.Constructive alignment

Pedagogical design in which the intended learning outcomes of a unit are mirrored both in the teaching and learning activities and the assessment. More details below.Assessment

Involves tasks to provide students the opportunity to apply and to demonstrate their learning They can take many forms from quizzes or tests/exams to team projects and case-studies. They can be formative – wherein the assessment involves constructive, developmental feedback on student progress, or summative – wherein the assessment is more focused on assessing student knowledge and capacity at the completion of their study in a unit.1Teaching Learning Tasks

These are the activities – what students and teachers do together in the classroom or another context – that provide opportunities for learning. TLAs can take many forms and need to be developed and used to support engaged and active leaning.

Development, refinement and approval of ULOs

Typically, a new course is approved for development by the Academic Board after a member of staff or a member of the executive has proposed a course for development. Typically, a business case would need to be developed and this would need to be approved by the Board of Directors.

Once approved for development, the actual development of the course and its constituent units is undertaken by the Course Advisory Committee, drawing on expertise as they or the Dean see fit. As part of the course development, a rationale and a series of Course Learning Outcomes will be proposed and refined. These become the drivers of further course and unit design and, as such, provide the pedagogical frame for the development of each individual unit through the development of a unit outline – its aims, learning outcomes assessment structure, topic list and references.2 It would be unusual for the teaching learning activities of a unit to be determined through this development process but it does occasionally happen. This can sometimes help with the refinement of constructive alignment.

A Course Coordinator or the Dean oversee the process of course and unit development and must ensure that learning outcomes and constructive alignment are developed in the appropriate way and to the appropriate standard.Pedagogical and conceptual framework for developing ULOs

The end point of the process of developing a ULO statement should be several phrases that complete the following sentence: On successful completion of this unit students, will be able to …

Such a statement does several things. It,Captures and explains the central reason for the unit being a component of the course.

Focuses the unit design on student learning (rather than teaching or the work of the teacher) and, therefore, centres the educational experience of the unit on the student. This is student-centred teaching.

Tells the student explicitly what it is they will learn if they complete the unit successfully.

Assures educational quality in that it states clearly what the outcome of the educational process of a unit will be for the student and how it is aligned with the course learning outcomes.

A word about ‘successful completion’: The modifying of the noun ‘completion’ by the adjective ‘successful’ makes it clear to all involved that the student has a responsibility to complete what is required in the unit and to do this at the pass level to be considered to have attained the learning outcomes. A reciprocal responsibility is expressed implicitly here: that the unit is designed and delivered in such a way as to provide guided learning opportunities to the student so that they can learn what is necessary to attain the learning outcomes.

This reciprocal set of responsibilities means that we, as those who develop and teach units, must align the teaching and learning components of units constructively.

Biggs and Tang (2011: 113- 132) provide a detailed and well-scaffolded guide to the development of learning outcomes for individual units (they refer to them as ‘courses’). We have used their work, the work of others and the requirements of regulators to inform the process as it should be undertaken at CIHE. Staff are encouraged to supplement this kit through a close consideration of Biggs and Tang.

A clarifying comparison: Biggs and Tang offer an example of the difference between a unit objective and a learning outcome. Objectives are often teacher-centered and less aligned (‘To provide an understanding…’; or ‘to develop an understanding …’ (adapted from Biggs and Tang); whereas, Learning Outcomes articulate activity – the ‘doings’ that are evidence of more cognitive and perceptual attainments. This is a key element of the QA provided by constructively aligned learning outcomes – they are articulations through verbs of action of the levels of understanding or skill attained. The Assessment at CIHE papers discuss how such learning outcomes link to the development of assessment that is criteria and standards based.

Verbs do a lot of work in the model of CA as developed by Biggs and now dominant in many contexts of undergraduate education. For Biggs and Tang (2011), outcome statements specify a ‘verb that informs the student how they are expected to change as a result of learning’ (98) and, as implied above, the inclusion of the verb in the text of ULOs and in the TLAs and assessment achieves alignment. It is not that simple: proper, thorough-going pedagogical design, execution and monitoring are necessary to ensure constructive alignment is enacted through sound, reflexive educational activity by teaching staff. Writing ULOs is the first step. The other papers in this kit and in the Assessment at CIHE series outline the other dimensions to CA pedagogy as it is to be undertaken at CIHE.

Writing ULOs

To write a series of ULOs, it is recommended that the unit developer or developers,Decide what knowledge or skills are intended to be learnt, by students in the unit. Make sure to focus on the core, essential knowledge and skills that underscore the reason for the unit’s place in the course.

If the knowledge is more declarative (students need to know or understand something), consider how this knowledge or understanding can and should be demonstrated. For example, ‘understand the role of accounting standards in accounting practice’ articulates knowledge but not how it can be demonstrated. ‘Apply accounting standards to the analysis of …’ articulates the way a student will be required to show they understand through application. This formulation has the added benefit of grounding the knowledge they are acquiring in developing professional practice.

If the knowledge is more functioning, that is, it is more directly related to the demonstration of skills – the capacity to do something, then the selection of verbs is more direct and straightforward.

The final formulation of a draft ULO(s) should include a well selected activity-focused verb that aligns with the required level of the unit. This should be linked to a very clear formulation of the knowledge, content or skill that is meant to be demonstrated.

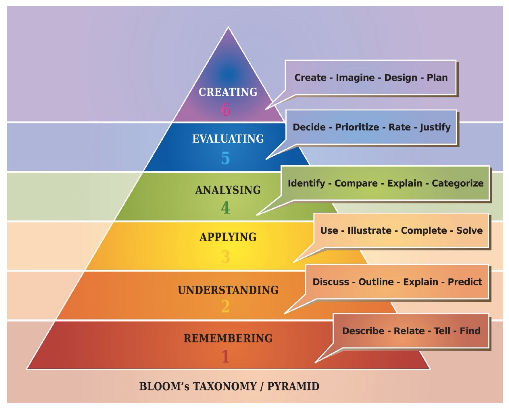

Bloom’s taxonomy (see appendix) is often used as the conceptual framework for deciding on formulations of ULOs. This structure helps articulate the nature and level of activity specified by the verb used in a ULO but it is not definitive nor is it universally applicable. Staff should collaborate on the development of ULOs to help determine the best, most salient descriptions.

Biggs and Tang’s Chapter 7 has a well-structured process that staff can follow to develop ULOs.

Part 2: Teaching Learning Activities and Constructive Alignment Monitoring Tool

This document is designed to assist CIHE academic teaching staff in developing, implementing and monitoring constructively aligned Teaching/Learning Activities (TLAs).

The framework used here is drawn from Biggs and Tang 2011 and interested staff are directed to this book for a fuller discussion of the theory and approach underlying the work outlined in this kit.

At CIHE we aim for outcomes-based teaching learning that is constructively aligned.

At CIHE all of our units have a statement of learning outcomes. These outline what students should be able to do after the teaching in a unit.

In constructive alignment we ‘systematically align the teaching/learning activities, as well as the assessment tasks, to the intended learning outcomes.’ (Biggs and Tang 2011: 11)

Staff should refer to the series of Assessment at CIHE papers for a discussion of the approach to assessment at CIHE and the ways in which assessment design and delivery should be aligned to learning outcomes. In brief, assessment, formative and summative, is used to see how well students are performing. It provides a monitoring and feedback mechanism for students and staff. At CIHE we use criteria and standards, linked to unit learning outcomes, to align assessment tasks to the learning we intend for our students. As the Assessment at CIHE series explains, the specification of criteria and standards is used not simply as an evaluation mechanism but should be integrated into teaching processes, especially in classes that either outline assessment demands to students or deliver feedback for formative development of student attainment of learning outcomes. Assessment and TLAs, of course, work in sync in the delivery of units of study. Each should be aligned to learning outcomes.

This kit focuses on TLAs – their development and monitored implementation. TLAs should be selected/developed so as to engage students in the kind of learning that will best facilitate their attainment of the knowledge and skills outlined in a unit’s learning outcome statement.

The intention of the kit is to provide staff with a mechanism for ‘reflexive practice’ in their teaching at CIHE. Reflexive practice involves a process of reflecting on your own work, using theories and ideas that are useful to analyse and interpret your pedagogical (theory and practice) toward a more thoughtful and informed continual re/development and improvement of you work. Reflexive practice has been determined to be strongly correlated with effective undergraduate teaching.

The kit is designed to assist in the articulation of the alignment between learning activities and proposed TLAs, providing a ‘worksheet’ for the explication of TLAs and the learning experience they intend to provide. This explication of the TLAs is then to be linked to or ‘aligned’ explicitly to one or more of the learning outcomes of the unit of study. It is possible at this stage to also further articulate the alignment of the TLA to assessment requirements, outlining how the TLA will support the development of knowledge or skills required for assessment tasks.

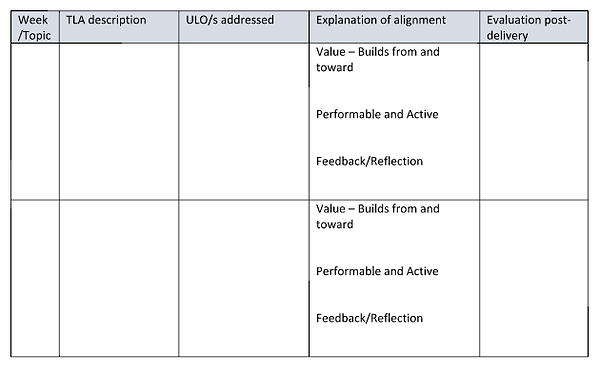

This grid is to be used for planning/drafting intended TLAs. It is expected that one TLA per teaching week be planned and monitored using this grid.

In developing TLAs, consider the guidelines set down by Biggs and Tang. This list is based on Biggs and Tang and ‘translates’ some of their ideas. Staff should ensure that they address most, if not all, of these criteria in their development of TLAs.

TLAs should:

Have value

Students should be able to see how the activity aligns with one or more learning outcome for the unit.Require students to build on what they already know

Students should be able to use knowledge or skill already developed and identifiable to participate in the activity.

1 and 2 address the way in which a TLA should build from existing knowledge toward the attainment of a learning outcome.Be readily performable

Students should be able to perform the activity – it should not be beyond them or too straightforward.Be relevantly active

The activity should involve more than reading and writing – group work, interaction, movement, forms of creativity etc. will enhance student learning.

3 and 4 address the way in which students should be actively involved and appropriately capable of what they are asked to do in an activity.Include some mechanism for formative feedback

Whether the lecturer is providing comment and critique or whether this is provided by student peers, all activities should involve some feedback that identifies how students are progressing toward the achievement of learning outcomes. This can be combined with 6 –Involve students in monitoring and reflecting on their own learning

As with 5, students should reflect on their learning, either with peers or with the lecturer. It is also useful for the lecturers own reflexive practice to seek feedback on the TLA and how students experienced it as a learning process.

5 and 6 are essential for active, effective learning – feedback and reflection work hand in hand to promote engaged learning.

For the purposes of planning and monitoring, these categories have been combined:

Value – Builds from and toward

Performable and Active

Feedback/Reflection

The grid is available as an Excel spreadsheet which should be used by staff to plan and evaluate TLA constructive alignment.

TLA planning and monitoring grid

Part 3: Assessment and Constructive Alignment Monitoring Tool

This is one tool in the CA kit that is designed to assist CIHE academic teaching staff to develop, implement and monitor constructively aligned in units of study.

As with the other parts of this constructive alignment kit, the principles that guide constructive alignment of assessment with unit learning outcomes are drawn from Biggs and Tang 2011 with modifications and specifications for the approach to CA as developed and adopted at CIHE. Interested staff members are encourage to read Biggs and Tang.

This part of the kit should also be read in conjunction with the more elaborated discussion of the approach to assessment at CIEH elaborated in the Assessment at CIHE papers.

Biggs and Tang suggest that ‘assessment tasks should comprise an authentic representation of the course (for us, unit) learning outcomes’. (190, my emphasis) In this part of the CA toolkit we address how it is this might be achieved in the development of assessment. This principle also underscores the monitoring tool introduced below.

Some critical thoughts first:

The notion of authentic as used by Biggs and Tang (2011) is specific and we will address this below. However, from the outset, it should be noted that this insider specificity could create ambiguity. Staff are encouraged to keep Biggs and Tang’s (2011) definition of ‘authentic’ as it relates to assessment in mind as they think about how to develop and monitor constructively aligned assessment.

The word representation is highly ambiguous. Given Biggs and Tang ‘s (2011) focus on verb choice in writing ULOs and criteria, staff are asked to keep in mind that the idea of a verb capturing the complete picture of what a student does or thinks or understands etc. is flawed. We use these verbs to capture a sense of what is done or thought etc. but we must accept that no one verb can capture the complete range of human activity that might be required of a unit’s skills and knowledge or the performance required in an assessment. Nonetheless, the centrality of verbs (often singularly) to the discourse of ULOs and CA is such that we will work with an imperfect system.

To make the ULO and CA approach work effectively and realistically, the tool introduced below will assist staff in digging below what might or might not be captured in verbs, requiring an explication of the knowledge and skill necessary in assessment tasks and articulating this more robustly to ULOS.

What is assessment from the student’s point of view?

Assessment often, as Ramsden suggests, ‘defines actual curriculum.’ (Ramsden 1992:187, cited by Biggs and Tang 2011)

Issues that need to be cautiously observed and mitigated against are:

The behaviour of students, whereby they work principally with an eye on what they need to do to complete assessment tasks with little regard for the other aspects of the curriculum or of the pedagogical processes in which they are involved.

The behaviour of staff that might involve them either ‘teaching to the assessment,’ that is, concentrating in their teaching practice principally on the knowledge and skills required for the assessment tasks, or using assessment as a driver for curriculum and pedagogy, that is, where curriculum and pedagogy are used in what Biggs and Tang (2011) describe as a ‘backwash,’ determining the structure of a curriculum and the pedagogical processes used. The second is a more extreme version of the backwash process. Both are risks to the quality of education even if they happen within a frame of quality assured education.

Biggs and Tang (2011) suggest that the mitigation to deal with both these risks is properly constructed assessment that is aligned to ULOs. In this way, aligned assessment becomes a principle part of the learning in which students engage. They suggest that, if learning outcomes are embedded in assessment then ‘[i]n preparing for the assessment, students will be learning the intended outcomes.’ (198)

There are flaws in Biggs and Tang’s (2011) accumulating logic: Number 1 above is, in a sense, the student’s responsibility though good planning and effective delivery can mitigate the effect of such dispositions to learning. And, realistically, there will always be some students for whom the focus is on completing assessment to pass a unit. It is not reasonable to expect staff to capture the attention and motivate all students all of the time. The real logical and pedagogical problem comes when we consider number 2 above (the backwash problems) and the limitations of linguistic choices to fully capture the art, craft and engineering involved in effective pedagogy: There is something inevitably reductive about the ideas that a. we can capture in words all that is to be learned and/or being performed in/through assessment, and b. even the most comprehensively designed assessment task can require the performance of any or all learning outcomes in some full way. This is too big a burden to place on assessment tasks alone and it reduces educational processes and learning experiences dangerously.

Nonetheless, we must work within the frameworks that hold currency in the literature and for regulators.

We are best to accept the challenge that learning outcomes can, on the whole, capture the breadth and depth of learning in a unit and that, again more or less, that assessments can be logically and coherently aligned to ULOS.

Key terms

Biggs and Tang (2011) construct and operationalise three key binaries:

- A distinction between declarative and functioning knowledge and

- A distinction between measurement and standards as models of assessment, and

- Formative versus summative assessment. Each can be critiqued but, again, the critique should be seen as enlivening our use of the CA framework at CIHE rather than as suggesting we shouldn’t engage in CA.

Declarative knowledge is content knowledge – what a student knows about particular topic or area of study, broad or narrow. Biggs and Tang (2011) also suggest that declarative knowledge is decontextualized. Functioning knowledge is what a student can do – their performance of understanding in context. Arguably, functioning knowledge requires declarative knowledge. At CIHE you will probably find that these two kinds of knowledge a woven together and interdependent in the subject areas that we teach.

Biggs and Tang (2011) contrast two kinds of assessment – measurement and standards. Whilst the distinction is rhetorically useful in their writing, in an institution that must necessarily measure students’ knowledge of content (laws, formulae, nomenclature etc.) for professional reasons and for the effectiveness of iteratively designed and scaffolded assessment, measurement becomes part of a more complete, longer term process of assessment and, at times, is a crucial aspect of an assessment that may ‘look’ more standards-based such as a case-study that requires students to demonstrate knowledge that is measurable (an accounting process or a legal precedent) as well as being able to work more holistically and to problem solve and critically engage with an accounting practice in the context of contemporary accounting.

Formative and summative assessment are used to distinguish between, on one hand, assessment that provides feedback and informs ongoing learning – students are expected to learn from their identified mistakes and failings and improve their performance in subsequent assessment tasks (formative); and, on the other hand, assessment that is more ‘teacher centred’ as is used to assess how complete a student’s knowledge is at the completion of a period of study, typically understood as a unit of study (for Biggs and Tang 2011, a ‘course’). This distinction is more sustainable in some forms of assessment than others. Even a mark and grade on an exam tells a student something of what they have mastered and whether or not then need to improve. Certainly, a decent mark in a final exam in a basic accounting unit tells a student that they are prepared for the next step in developing their knowledge. And, a formative assessment is only as good as the feedback and, probably just as importantly, as good as the use to which a student puts the feedback they are provided.

How to deal with these reductions used in these theoretical principles?

It is probably most useful to see these binaries as continua: each is probably operating in

each and every assessment task and descriptions should capture the emphases or

weightings involved in each assessment along these continua.

You are encouraged to use them as descriptors but do not feel that each one excludes the

other; document your decision making as part of the CA monitoring process.

The CIHE standards model

At CIHE, our policy determines a to use of criteria and standards the specification of assessment requirements and marking guides/rubrics and a criteria and standards approach is used in the 3 step assessment moderation process stipulated by our Quality Assurance Framework.

The standards model of assessment does not compare students but measure student performance in assessment against a set of standards (criteria) 4 linked to ULOs:

If the intended learning outcomes are written appropriately, the job of the assessment is to enable us to state how well they have been met, the ‘how well’ being expressed not in ‘marks’ but in a hierarchy of levels, such as letter grades from ‘A’ to ‘D’, or as high distinction through credit to conditional pass, or whatever system of grading is used. Deciding at the level of a particular student performance is greatly facilitated by using explicit criteria or rubrics (…). These rubrics may address the task, or the intended learning outcome. (Biggs and Tang 2011: 207)

Designing constructively aligned assessment

An appropriate assessment task (…) should tell us how well a given student has achieved the ILO(s) (ULOs) it is meant to address and/or how well the task itself has been performed. Assessment tasks should not sidetrack students into adopting low-level strategies such as memorizing, question spotting and other dodges. The backwash must, in other words, be positive, not negative. It will be positive if alignment is achieved because then … the assessment tasks require students to perform what the ILOs (ULOs) specify as intended for them to learn. (Biggs and Tang 2011: 224)

In designing assessment tasks, staff should outline:

The specific criteria that will be used to assess a student’s performance.

The way in which the criteria articulate to one or more ULO using a listing or description of the specific evidence that will be required of the student’s achievement in the form of standards for each criterion.

Staff should also consider:

The ‘weighting’ of the assessment in terms of the required time spent on task, the coverage of the ULOs and the place in the assessment scaffold/iteration across the unit.

The manageability of the task for students producing the assessment and staff in marking and being able to provide effective feedback.

Remember

When assessing students, we are always assessing their demonstration or performance of unit

learning outcomes.

Designing assessments and determining their criteria and standards should be done in such a

way that it reassures you that you can make an informed decision about student attainment of

the ULOs.

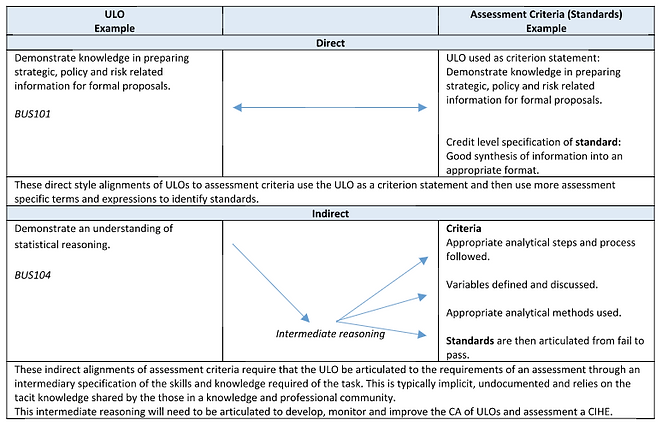

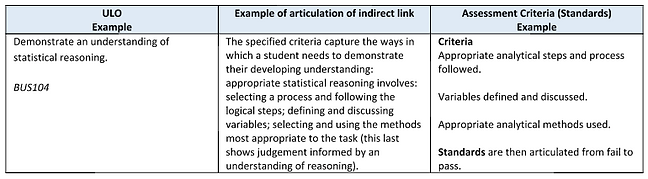

ULO-Assessment alignment at CIHE relies on the articulation of the link between the ULO and the assessment criteria (and its standards) that is expected to show a lecturer that the student has performed the required skill or demonstrated the required knowledge.

The following diagram displays the key piece in the articulation of ULO-Assessment alignment:

It is not expected that staff will develop explanations of every one of these indirect links. It is, however, expected that staff will provide some documented reasoning of this kind for each assessment, perhaps selecting some key criteria to explore in this way for each assessment each semester, accumulating a more complete picture over time.

This documenting of reasoning should be used to

-

monitor the development of assessment when each task is being prepared (this should form part of the moderation process)

-

evaluate the effectiveness of the assessment as a reflective exercise once it has been delivered, using any issues or insights from application of criteria and standards during the assessment delivery and grading process, and

-

present the assessment monitoring aspects of the unit report at the end of semester.

There is a pre-formatted spreadsheet available to staff for their record keeping. The first sheet allows for the list of the alignment in the unit outline and an assessment of direct or indirect alignment.

The second sheet is a tool for articulating the reasoning for criteria that have a more indirect alignment relationship to the ULOs as shown above.

-

An assessment in a properly designed and scaffolded course is never purely summative. Assessment should always

- provide an opportunity for students to reflect on their own learning and attainment of outcomes, and

-

form the basis of further learning through application either in a formal educational context or in a professional or life context.

-

The process of course and unit development is outlined in the … policies and there are templates that are required for the development of a formal course proposal and for the development of unit outlines.

-

The need to understand and emphasise this responsibility is the reason for the ordering of the words as ‘Teaching & Learning’ at CIHE – we take seriously our role in designing and delivering units to make sure they provide guided learning opportunities for students so that they can learn what is necessary in order to attain the learning outcomes.

-

This nomenclature can be confusing as the terms ‘criteria’ and ‘standards’ are used by various scholars and practitioners differently. At CIHE criteria are the domains of expertise, knowledge or skill being assess while standards describe the level of achievement in each of those domains. See ‘Assessment at CIHE: Criteria and Standards.’

References

Biggs, J. B. & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for quality learning at university: What the student does. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

Suggested further reading

Biggs, J. (2014). Constructive alignment in university teaching. HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 1(5), 5-22.

Biggs, J. (2003). Aligning teaching for constructing learning. Higher Education Academy, 1-4.

McCune, V., & Entwistle, N. (2011). Cultivating the disposition to understand in 21st century university education. Learning and Individual Differences, 21(3), 303 310.

Treleaven, L., & Voola, R. (2008). Integrating the development of graduate attributes through constructive alignment. Journal of marketing education, 30(2), 160 173.

Walsh, A. (2007). An exploration of Biggs’ constructive alignment in the context of work‐based learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 32(1), 79 87.

Appendix: Bloom’s taxonomy

http://www.vcamp360.com/learning-management- system-definition- and-blooms- taxonomy/ accessed July 28 2017